With the advent of social media, and the Babylonian deluge of tweets, YouTube comments, and wall posts traversing the internet daily, text-mining has become an increasingly important tool of the data scientist. Basically, all of these tweets, Facebook posts, etc. form a valuable and robust set of data, and text-mining helps us understand what it all really means. Universal Studios might mine text to process mass reviews of its latest movie on social media; Ryanair might mine text to gauge just how shitty the public thinks its service really is. In this post, I set out to understand what South America stands for, or purportedly stands for, as a whole.

To do this, I first choose a set of data, and what better source than the documents that govern the countries themselves? Then, using R's "tm" (short for text-mining) package, I can easily process these documents and see what they have to offer.

The countries considered in this analysis are only those that are Spanish-speaking: Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay, and Venezuela. If we were to include the remaining four - Guyana, French Guiana, Suriname and Brazil - we'd have to obtain a translation of their constitutions, so in order keep our analysis unaffected by pure lingual differences as well as translational inaccuracies, I've decided to omit them altogether.

To begin, we first copy and paste each constitution from Georgetown's Center for Latin American Studies (and that of Venezuela from the Venezuela Supreme Court's website) into separate TextEdit documents. We then save each as a UTF-8 encoded .txt file (note to self and others: this step is very important). From there, we move to R.

The documents are first loaded and then cleaned. To clean, spanish stop-words are removed - words like "el, en, porque" or "the, in, because" in English. In addition, we remove a few other words that are particularly universal/inconsequential, namely "ley, artículo, caso, estado, nacional, nación, constitución," or "law, article, case, state, national, nation, constitution," respectively.

Next, we make everything lowercase, and remove numbers and punctuation. Lastly, we convert the text into a term-document-matrix, where the number of occurrences of each word in each document is calculated and put into a matrix. A "TDM" is generally the all-things-possible starting point of a text-mining analysis.

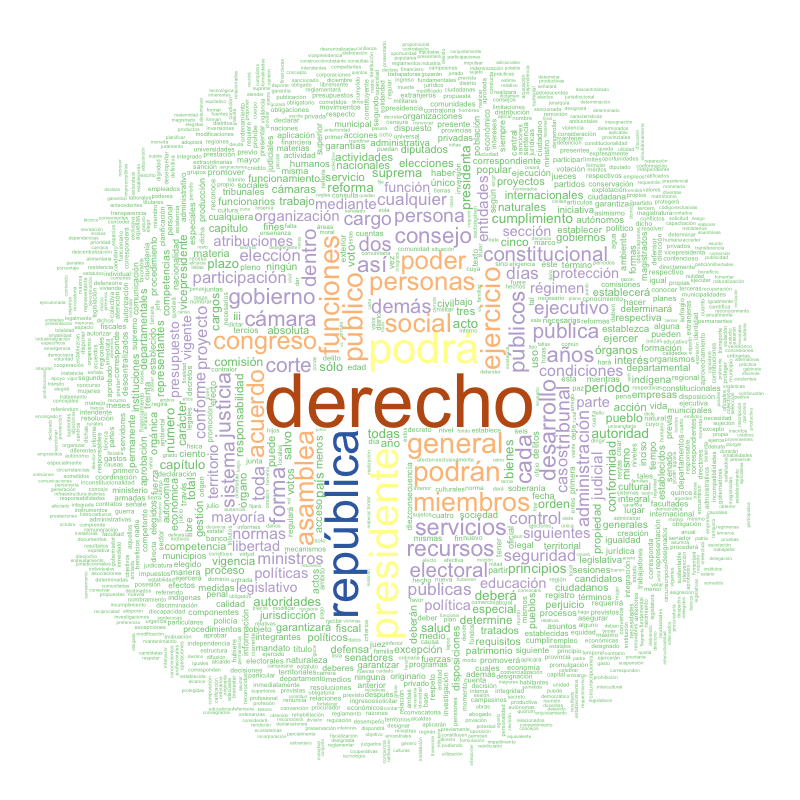

From there, we visualize! For this visualization, I choose to create a word-cloud with R's "wordcloud" package, and only include words that occur 20 times or more across the 9 constitutions. The bigger words occur more frequently, and vice versa. The biggest word, "derecho," therefore occurs most frequently across the documents.

So, what do we have? Again, "derecho," or "right" (as in your "right" as a citizen) is used most frequently. In addition, it appears that the majority of countries have presidents, as the word "presidente" is rather large, as well as consider themselves republics, as the word "república" is large as well. Interestingly, we see in yellow that the word "podrá" is used frequently, a future-tense verb meaning "will be able to"; why is this word used instead of "puede," a present-tense conjugation of the same verb meaning "is now able to?" Given that most of these countries gained independence from Spain in the last 200 years, perhaps this small caveat is a reflection of founders' general apprehension for their country's future and true independence?

As one can see, a word-cloud is a really nice visualization of a given text, or commonalities between multiple texts. While it's really only a high-level view of the data at hand, it does paint a rather pretty picture.