Roughly speaking, my machine learning journey began on Kaggle. "There's data, a model (i.e. estimator) and a loss function to optimize," I learned. "Regression models predict continuous-valued real numbers; classification models predict 'red,' 'green,' 'blue.' Typically, the former employs the mean squared error or mean absolute error; the latter, the cross-entropy loss. Stochastic gradient descent updates the model's parameters to drive these losses down." Furthermore, to fit these models, just import sklearn.

A dexterity with the above is often sufficient for—at least from a technical stance—both employment and impact as a data scientist. In industry, commonplace prediction and inference problems—binary churn, credit scoring, product recommendation and A/B testing, for example—are easily matched with an off-the-shelf algorithm plus proficient data scientist for a measurable boost to the company's bottom line. In a vacuum I think this is fine: the winning driver does not need to know how to build the car. Surely, I've been this person before.

Once fluid with "scikit-learn fit and predict," I turned to statistics. I was always aware that the two were related, yet figured them ultimately parallel sub-fields of my job. With the former, I build classification models; with the latter, I infer signup counts with the Poisson distribution and MCMC—right?

Before long, I dove deeper into machine learning—reading textbooks, papers and source code and writing this blog. Therein, I began to come across terms I didn't understand used to describe the things that I did. "I understand what the categorical cross-entropy loss is, what it does and how it's defined," for example: "why are you calling it the negative log-likelihood?"

Marginally wiser, I now know two truths about the above:

- Techniques we anoint as "machine learning"—classification and regression models, notably—have their underpinnings almost entirely in statistics. For this reason, terminology often flows between the two.

- None of this stuff is new.

The goal of this post is to take three models we know, love, and know how to use and explain what's really going on underneath the hood. I will assume the reader is familiar with concepts in both machine learning and statistics, and comes in search of a deeper understanding of the connections therein. There will be math—but only as much as necessary. Most of the derivations can be skipped without consequence.

When deploying a predictive model in a production setting, it is generally in our best interest to import sklearn, i.e. use a model that someone else has built. This is something we already know how to do. As such, this post will start and end here: your head is currently above water; we're going to dive into the pool, touch the bottom, then work our way back to the surface. Lemmas will be written in bold.

First, let's meet our three protagonists. We'll define them in Keras for the illustrative purpose of a unified and idiomatic API.

Linear regression with mean squared error

input = Input(shape=(10,))

output = Dense(1)(input)

model = Model(input, output)

model.compile(optimizer=_, loss='mean_squared_error')

Logistic regression with binary cross-entropy loss

input = Input(shape=(10,))

output = Dense(1, activation='sigmoid')(input)

model = Model(input, output)

model.compile(optimizer=_, loss='binary_crossentropy')

Softmax regression with categorical cross-entropy loss

input = Input(shape=(10,))

output = Dense(3, activation='softmax')(input)

model = Model(input, output)

model.compile(optimizer=_, loss='categorical_crossentropy')

Next, we'll select four components key to each: its response variable, functional form, loss function and loss function plus regularization term. For each model, we'll describe the statistical underpinnings of each component—the steps on the ladder towards the surface of the pool.

Before diving in, we'll need to define a few important concepts.

Random variable

I define a random variable as "a thing that can take on a bunch of different values."

- "The tenure of despotic rulers in Central Africa" is a random variable. It could take on values of 25.73 years, 14.12 years, 8.99 years, ad infinitum; it could not take on values of 1.12 million years, nor -5 years.

- "The height of the next person to leave the supermarket" is a random variable.

- "The color of shirt I wear on Mondays" is a random variable. (Incidentally, this one only has ~3 distinct values.)

Probability distribution

A probability distribution is a lookup table for the likelihood of observing each unique value of a random variable. Assuming a given variable can take on values in \(\{\text{rain, snow, sleet, hail}\}\), the following is a valid probability distribution:

p = {'rain': .14, 'snow': .37, 'sleet': .03, 'hail': .46}

Trivially, these values must sum to 1.

- A probability mass function is a probability distribution for a discrete-valued random variable.

- A probability density function gives a probability distribution for a continuous-valued random variable.

- Gives, because this function itself is not a lookup table. Given a random variable that takes on values in \([0, 1]\), we do not and cannot define \(\Pr(X = 0.01)\), \(\Pr(X = 0.001)\), \(\Pr(X = 0.0001)\), etc.

- Instead, we define a function that tells us the probability of observing a value within a certain range, i.e. \(\Pr(0.01 < X < .4)\).

- This is the probability density function, where \(\Pr(0 \leq X \leq 1) = 1\).

Entropy

Entropy quantifies the number of ways we can reach a given outcome. Imagine 8 friends are splitting into 2 taxis en route to a Broadway show. Consider the following two scenarios:

- Four friends climb into each taxi. We could accomplish this with the following assignments:

# fill the first, then the second

assignment_1 = [1, 1, 1, 1, 2, 2, 2, 2]

# alternate assignments

assignment_2 = [1, 2, 1, 2, 1, 2, 1, 2]

# alternate assignments in batches of two

assignment_3 = [1, 1, 2, 2, 1, 1, 2, 2]

# etc.

- All friends climb into the first taxi. There is only one possible assignment.

assignment_1 = [1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1]

(In this case, the Broadway show is probably in West Africa or a similar part of the world.)

Since there are more ways to reach the first outcome than there are the second, the first outcome has a higher entropy.

More explicitly

We compute entropy for probability distributions. This computation is given as:

where:

- There are \(n\) distinct events.

- Each event \(i\) has probability \(p_i\).

Entropy is the weighted-average log probability over possible events—this much reads directly from the equation—which measures the uncertainty inherent in their probability distribution. The higher the entropy, the less certain we are about the value we're going to get.

Let's calculate the entropy of our distribution above.

p = {'rain': .14, 'snow': .37, 'sleet': .03, 'hail': .46}

def entropy(prob_dist):

return -sum([ p*log(p) for p in prob_dist.values() ])

In [1]: entropy(p)

Out[1]: 1.1055291211185652

For comparison, let's assume two more distributions and calculate their respective entropies.

p_2 = {'rain': .01, 'snow': .37, 'sleet': .03, 'hail': .59}

p_3 = {'rain': .01, 'snow': .01, 'sleet': .03, 'hail': .95}

In [2]: entropy(p_2)

Out[2]: 0.8304250977453105

In [3]: entropy(p_3)

Out[3]: 0.2460287703075343

In the first distribution, we are least certain as to what tomorrow's weather will bring. As such, this has the highest entropy. In the third distribution, we are almost certain it's going to hail. As such, this has the lowest entropy.

Finally, it is a probability distribution that dictates the different taxi assignments just above. A distribution for a random variable that has many possible outcomes has a higher entropy than a distribution that gives only one.

Now, let's dive into the pool. We'll start at the bottom and work our way back to the top.

Response variable

Roughly speaking, each model looks as follows. It is a diamond that receives an input and produces an output.

The models differ in the type of response variable they predict, i.e. the \(y\).

- Linear regression predicts a continuous-valued real number. Let's call it

temperature. - Logistic regression predicts a binary label. Let's call it

cat or dog. - Softmax regression predicts a multi-class label. Let's call it

red or green or blue.

In each model, the response variable can take on a bunch of different values. In other words, they are random variables. What probability distribution is associated with each?

Unfortunately, we don't know. All we do know, in fact, is the following:

temperaturehas an underlying true mean \(\mu \in (-\infty, \infty)\) and variance \(\sigma^2 \in (0, \infty)\).cat or dogtakes on the valuecatordog. The likelihood of observing each outcome does not change over time, in the same way that \(\Pr(\text{heads})\) for a fair coin is always \(0.5\).red or green or bluetakes on the valueredorgreenorblue. The likelihood of observing each outcome does not change over time, in the same way that the probability of rolling a given number on a fair die is always \(\frac{1}{6}\).

For clarity, each one of these assumptions is utterly banal. Nonetheless, can we use them nonetheless to select probability distributions for our random variables?

Maximum entropy distributions

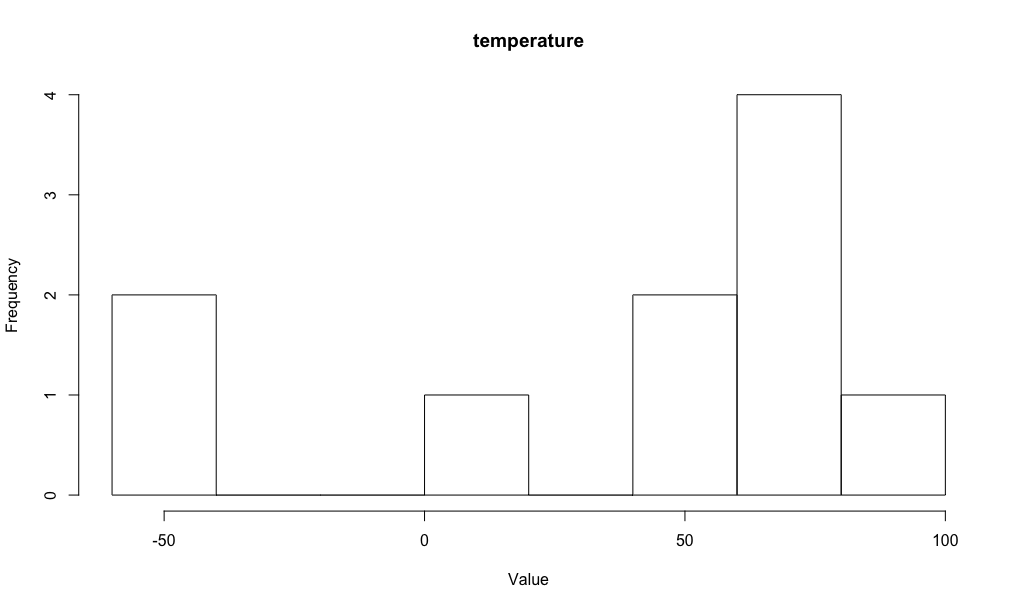

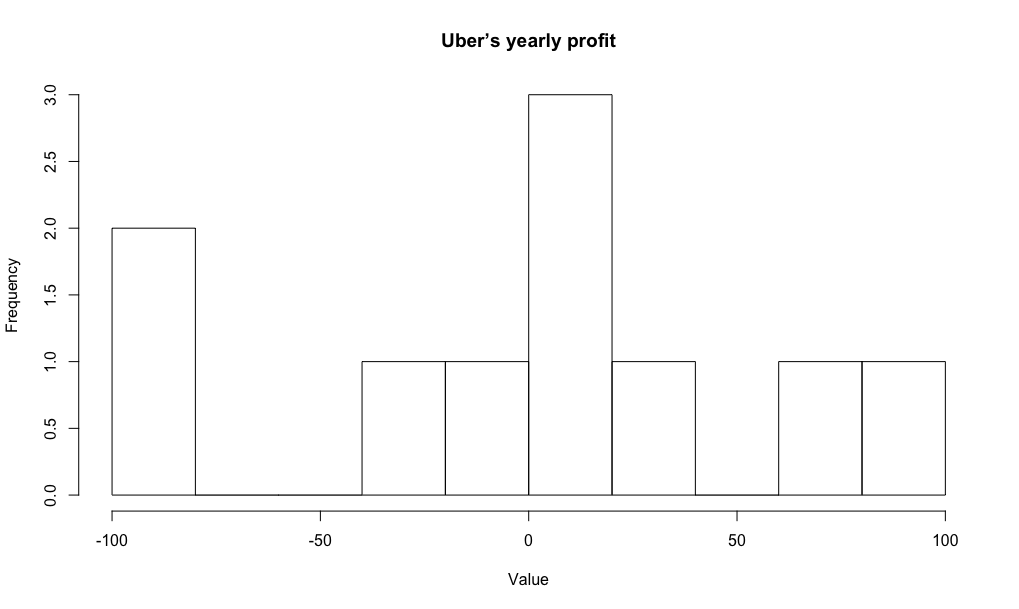

Consider another continuous-valued random variable: "Uber's yearly profit." Like temperature, it also has an underlying true mean \(\mu \in (-\infty, \infty)\) and variance \(\sigma^2 \in (0, \infty)\). Trivially, the respective means and variances will be different. Assume we observe 10 (fictional) values of each that look as follows:

| uber | temperature |

|---|---|

| -100 | -50 |

| -80 | 5 |

| -20 | 56 |

| 5 | 65 |

| 15 | 62 |

| -10 | 63 |

| 22 | 60 |

| 12 | 78 |

| 70 | 100 |

| 100 | -43 |

Plotting, we get:

We are not given the true underlying probability distribution associated with each random variable—not its general "shape," nor the parameters that control this shape. We will never be given these things, in fact: the point of statistics is to infer what they are.

To make an initial choice we keep two things in mind:

- We'd like to be conservative. We've only seen ten values of "Uber's yearly profit;" we don't want to discount the fact that the next twenty could fall into \([-60, -50]\) just because they haven't yet been observed.

- We need to choose the same probability distribution "shape" for both random variables, as we've made identical assumptions for each.

As such, we'd like the most conservative distribution that obeys the "utterly banal" constraints stated above. This is the maximum entropy distribution.

For temperature, the maximum entropy distribution is the Gaussian distribution. Its probability density function is given as:

For cat or dog, it is the binomial distribution. Its probability mass function (for a single observation) is given as:

(I've written the probability of the positive event as \(\phi\), e.g. \(\phi = .5\) for a fair coin.)

For red or green or blue, it is the multinomial distribution. Its probability mass function (for a single observation) is given as:

While it may seem like we've "waved our hands" over the connection between the stated equality constraints for the response variable of each model and the respective distributions we've selected, it is Lagrange multipliers that succinctly and algebraically bridge this gap. This post gives a terrific example of this derivation. I've chosen to omit it as I did not feel it would contribute to the clarity nor direction of this post.

Finally, while we do assume that a Gaussian dictates the true distribution of values of both "Uber's yearly profit" and temperature, it is, trivially, a different Gaussian for each. This is because each random variable has its own true underlying mean and variance. These values make the respective Gaussians taller or wider—shifted left or shifted right.

Functional form

Our three protagonists generate predictions via distinct functions: the identity function (i.e. a no-op), the sigmoid function and the softmax function, respectively. The Keras output layers make this clear:

output = Dense(1)(input)

output = Dense(1, activation='sigmoid')(input)

output = Dense(3, activation='softmax')(input)

In this section, I'd like to:

- Show how each of the Gaussian, binomial and multinomial distributions can be reduced to the same functional form.

- Show how this common functional form allows us to naturally derive the output functions for our three protagonist models.

Exponential family distributions

In probability and statistics, an "exponential family" is a set of probability distributions of a certain form, specified below. This special form is chosen for mathematical convenience, on account of some useful algebraic properties, as well as for generality, as exponential families are in a sense very natural sets of distributions to consider.

— Wikipedia

I don't relish quoting this paragraph—and especially one so deliriously ambiguous. This said, the reality is that exponential functions provide, at a minimum, a unifying framework for deriving the canonical activation and loss functions we've come to know and love. To move forward, we simply have to cede that the "mathematical conveniences, on account of some useful algebraic properties, etc." that motivate this "certain form" are not totally heinous nor misguided.

A distribution belongs to the exponential family if it can be written in the following form:

where:

- \(\eta\) is the canonical parameter of the distribution. (We will hereby work with the single-canonical-parameter exponential family form.)

- \(T(y)\) is the sufficient statistic. It is often the case that \(T(y) = y\).

- \(a(\eta)\) is the log partition function, which normalizes the distribution. (A more in-depth discussion of this normalizing constant can be found in a previous post of mine: Deriving the Softmax from First Principles.)

"A fixed choice of \(T\), \(a\) and \(b\) defines a family (or set) of distributions that is parameterized by \(\eta\); as we vary \(\eta\), we then get different distributions within this family."1 This simply means that a coin with \(\Pr(\text{heads}) = .6\) gives a different distribution over outcomes than one with \(\Pr(\text{heads}) = .7\). Easy.

Gaussian distribution

Since we're working with the single-parameter form, we'll assume that \(\sigma^2\) is known and equals \(1\).

where:

- \(\eta = \mu\)

- \(T(y) = y\)

- \(a(\eta) = \frac{1}{2}\mu^2\)

- \(b(y) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}}\exp{(-\frac{1}{2}y^2)}\)

Finally, we'll express \(a(\eta)\) in terms of \(\eta\) itself:

Binomial distribution

We previously defined the binomial distribution (for a single observation) in a crude, piecewise form. We'll now define it in a more compact form which will make it easier to show that it is a member of the exponential family. Again, \(\phi\) gives the probability of observing the true class, i.e. \(\Pr(\text{cat}) = .7 \implies \phi = .3\).

where:

- \(\eta = \log\bigg(\frac{\phi}{1-\phi}\bigg)\)

- \(T(y) = y\)

- \(a(\eta) = -\log(1-\phi)\)

- \(b(y) = 1\)

Finally, we'll express \(a(\eta)\) in terms of \(\eta\), i.e. the parameter that this distribution accepts:

You will recognize our expression for \(\phi\)—the probability of observing the true class—as the sigmoid function.

Multinomial distribution

Like the binomial distribution, we'll first rewrite the multinomial (for a single observation) in a more compact form. \(\pi\) gives a vector of class probabilities for the \(K\) classes; \(k\) denotes one of these classes.

This is almost pedantic: it says that \(\Pr(y=k)\) equals the probability of observing class \(k\). For example, given

p = {'rain': .14, 'snow': .37, 'sleet': .03, 'hail': .46}

we would compute:

Expanding into the exponential family form gives:

where:

- \(\eta_k = \log\bigg(\frac{\pi_k}{\pi_K}\bigg)\)

- \(T(y) = y\)

- \(a(\eta) = -\log(\pi_K)\)

- \(b(y) = 1\)

Finally, we'll express \(a(\eta)\) in terms of \(\eta\), i.e. the parameter that this distribution accepts:

Plugging back into the second line we get:

This you will recognize as the softmax function. (For a probabilistically-motivated derivation, please see a previous post.)

Finally:

Generalized linear models

Each protagonist model outputs a response variable that is distributed according to some (exponential family) distribution. However, the canonical parameter of this distribution, i.e. the thing we pass in, will vary per observation.

Consider the logistic regression model that's predicting cat or dog. If we input a picture of a cat, we'll output "cat" according to the stated distribution.

If we input a picture of a dog, we'll output "dog" according the same distribution.

Trivially, the \(\phi\) value must be different in each case. In the former, \(\phi\) should be small, such that we output "cat" with probability \(1 - \phi \approx 1\). In the latter, \(\phi\) should be large, such that we output "dog" with probability \(\phi \approx 1\).

So, what dictates the following?

- \(\mu_i\) in the case of linear regression, in which \(y_i \sim \mathcal{N}(\mu_i, \sigma^2)\)

- \(\phi_i\) in the case of logistic regression, in which \(y_i \sim \text{Binomial}(\phi_i, 1)\)

- \(\pi_i\) in the case of softmax regression, in which \(y_i \sim \text{Multinomial}(\pi_i, 1)\)

Here, I've introduced the subscript \(i\). This makes explicit the cat or dog dynamic from above: each input to a given model will result in its own canonical parameter being passed to the distribution on the response variable. (That logistic regression better make \(\phi_i \approx 0\) when looking at a picture of a cat!)

Finally, how do we go from a 10-feature input \(x\) to this canonical parameter? We take a linear combination:

Linear regression

\(\eta = \theta^Tx = \mu_i\). This is what we need for the normal distribution.

> The identity function (i.e a no-op) gives us the mean of the response variable. This mean is required by the normal distribution, which dictates the outcomes of the continuous-valued target \(y\).

Logistic regression

\(\eta = \theta^Tx = \log\bigg(\frac{\phi_i}{1-\phi_i}\bigg)\). To solve for \(\phi_i\), we solve for \(\phi_i\).

As you'll remember we did this above: \(\phi_i = \frac{1}{1 + e^{-\eta}}\).

> The sigmoid function gives us the probability that the response variable takes on the positive class. This probability is required by the binomial distribution, which dictates the outcomes of the binary target \(y\).

Softmax regression

\(\eta = \theta^Tx = \log\bigg(\frac{\pi_k}{\pi_K}\bigg)\). To solve for \(\pi_i\), i.e. the full vector of probabilities for observation \(i\), we solve for each individual probability \(\pi_{k, i}\) then put them in a list.

We did this above as well: \(\pi_{k, i} = \frac{e^{\eta_k}}{\sum\limits_{k=1}^K e^{\eta_k}}\). This is the softmax function.

> The softmax function gives us the probability that the response variable takes on each of the possible classes. This probability mass function is required by the multinomial distribution, which dictates the outcomes of the multi-class target \(y\).

Finally, why a linear model, i.e. why \(\eta = \theta^Tx\)?

Andrew Ng calls it a "design choice."1 I've motivated this formulation a bit in the softmax post. mathematicalmonk2 would probably have a more principled explanation than us both. For now, we'll make do with the following:

- A linear combination is perhaps the simplest way to consider the impact of each feature on the canonical parameter.

- A linear combination commands that either \(x\), or a function of \(x\), vary linearly with \(\eta\). As such, we could write our model as \(\eta = \theta^T\Phi(x)\), where \(\Phi\) applies some complex transformation to our features. This makes the "simplicity" of the linear combination less simple.

Loss function

We've now discussed how each response variable is generated, and how we compute the parameters for those distributions on a per-observation basis. Now, how do we quantify how good these parameters are?

To get us started, let's go back to predicting cat or dog. If we input a picture of a cat, we should compute \(\phi \approx 0\) given our binomial distribution.

A perfect computation gives \(\phi = 0\). The loss function quantifies how close we got.

Maximum likelihood estimation

Each of our three random variables receives a parameter—\(\mu, \phi\) and \(\pi\) respectively. We then pass in a \(y\): for discrete-valued random variables, the associated probability mass function tells us the probability of observing this value; for continuous-valued random variables, the associated probability density function tells us the density of the probability space around this value (a number proportional to the probability).

If we instead fix \(y\) and pass in varying parameter values, this same function becomes a likelihood function. It will tell us the likelihood of a given parameter having produced the now-fixed \(y\).

If this is not clear, consider the following example:

A Moroccan walks into a bar. He's wearing a football jersey that's missing a sleeve. He has a black eye, and blood on his jeans. How did he most likely spend his day?

- At home, reading a book.

- Training for a bicycle race.

- At the soccer game drinking beers with his friends—all of whom are MMA fighters that despise the other team.

We'd like to pick the parameter that most likely gave rise to our data. This is the maximum likelihood estimate. Mathematically, we define it as:

As we've now seen (ad nauseum), \(y\) depends on the parameter its generating random variable receives. Additionally, this parameter—\(\mu, \phi\) or \(\pi\)—is defined in terms of \(\eta\). Further, \(\eta = \theta^T x\). As such, \(y\) is a function of \(\theta\) and the observed data \(x\). This is perhaps the elementary truism of machine learning—you've known this since Day 1.

Since our observed data are fixed, \(\theta\) is the only thing that we can vary. Let's rewrite our argmax in these terms:

Finally, this expression gives the argmax over a single data point, i.e. training observation, \((x^{(i)}, y^{(i)})\). To give the likelihood over all observations (assuming they are independent of one another, i.e. the outcome of the first observation does not impact that of the third), we take the product.

The product of numbers in \([0, 1]\) gets very small, very quickly. Let's maximize the log-likelihood instead so we can work with sums.

Linear regression

Maximize the log-likelihood of the Gaussian distribution. Remember, \(x\) and \(\theta\) assemble to give \(\mu\), where \(\theta^Tx = \mu\).

Maximizing the log-likelihood of our data with respect to \(\theta\) is equivalent to maximizing the negative mean squared error between the observed \(y\) and our prediction thereof.

Notwithstanding, most optimization routines minimize. So, for practical purposes, we go the other way.

> Minimizing the negative log-likelihood of our data with respect to \(\theta\) is equivalent to minimizing the mean squared error between the observed \(y\) and our prediction thereof.

Logistic regression

Same thing.

Negative log-likelihood:

> Minimizing the negative log-likelihood of our data with respect to \(\theta\) is equivalent to minimizing the binary cross-entropy (i.e. binary log loss) between the observed \(y\) and our prediction of the probability thereof.

Multinomial distribution

Negative log-likelihood:

> Minimizing the negative log-likelihood of our data with respect to \(\theta\) is equivalent to minimizing the categorical cross-entropy (i.e. multi-class log loss) between the observed \(y\) and our prediction of the probability distribution thereof.

Maximum a posteriori estimation

When estimating \(\theta\) via the MLE, we put no constraints on the permissible values thereof. More explicitly, we allow \(\theta\) to be equally likely to assume any real number—be it \(0\), or \(10\), or \(-20\), or \(2.37 \times 10^{36}\).

In practice, this assumption is both unrealistic and impractical: typically, we do wish to constrain \(\theta\) (our weights) to a non-infinite range of values. We do this by putting a prior on \(\theta\). Whereas the MLE computes \(\underset{\theta}{\arg\max}\ P(y\vert x; \theta)\), the maximum a posteriori estimate, or MAP, computes \(\underset{\theta}{\arg\max}\ P(y\vert x; \theta)P(\theta)\).

As before, we start by taking the log. Our joint likelihood with prior now reads:

We dealt with the left term in the previous section. Now, we'll simply tack on the log-prior to the respective log-likelihoods.

As every element of \(\theta\) is a continuous-valued real number, let's assign it a Gaussian distribution with mean 0 and variance \(V\).

Our goal is to maximize this term plus the log-likelihood—or equivalently, minimize their opposite—with respect to \(\theta\). For a final step, let's discard the parts that don't include \(\theta\) itself.

This is L2 regularization. Furthermore, placing different prior distributions on \(\theta\) yields different regularization terms; notably, a Laplace prior gives the L1.

Linear regression

> Minimizing the negative log-likelihood of our data with respect to \(\theta\) given a Gaussian prior on \(\theta\) is equivalent to minimizing the mean squared error between the observed \(y\) and our prediction thereof, plus the sum of the squares of the elements of \(\theta\) itself.

Logistic regression

> Minimizing the negative log-likelihood of our data with respect to \(\theta\) given a Gaussian prior on \(\theta\) is equivalent to minimizing the binary cross-entropy (i.e. binary log loss) between the observed \(y\) and our prediction of the probability thereof, plus the sum of the squares of the elements of \(\theta\) itself.

Softmax regression

> Minimizing the negative log-likelihood of our data with respect to \(\theta\) given a Gaussian prior on \(\theta\) is equivalent to minimizing the categorical cross-entropy (i.e. multi-class log loss) between the observed \(y\) and our prediction of the probability distribution thereof, plus the sum of the squares of the elements of \(\theta\) itself.

Finally, in machine learning, we say that regularizing our weights ensures that "no weight becomes too large," i.e. too "influential" in predicting \(y\). In statistical terms, we can equivalently say that this term restricts the permissible values of these weights to a given interval. (Furthermore, this interval is dictated by the scaling constant \(C\), which intrinsically parameterizes the prior distribution itself.* In L2 regularization, this scaling constant gives the variance of the Gaussian.)

Going fully Bayesian

The key goal of a predictive model is to compute the following distribution:

By term, this reads:

- \(P(y\vert x, D)\): given historical data \(D = ((x^{(i)}, y^{(i)}), ..., (x^{(m)}, y^{(m)}))\), i.e. some training data, and a new observation \(x\), compute the distribution of the possible values of the response \(y\).

- In machine learning, we typically select a single value from this distribution, i.e. point estimate.

- \(P(y\vert x, D, \theta)\): given historical data \(D\), a new observation \(x\) and any plausible value of \(\theta\), i.e. perhaps not the optimal value, compute \(y\).

- This is given by the functional form of the model in question, i.e. \(y = \theta^Tx\) in the case of linear regression.

- \(P(\theta\vert x, D)\): given historical data \(D\) and a new observation \(x\), compute the distribution of the values of \(\theta\) that plausibly gave rise to our data.

- The \(x\) plays no part; it's simply there such that the expression under the integral factors correctly.

- In machine learning, we typically select the MLE or MAP estimate of that distribution, i.e. a single value, or point estimate.

In a perfect world, we'd do the following:

- Compute the full distribution over \(\theta\).

- With each value in this distribution and a new observation \(x\), compute \(y\).

- NB: \(\theta\) is an object which contains all of our weights. In 10-feature linear regression, it will have 10 elements. In a neural network, it could have millions.

- We now have a full distribution over the possible values of the response \(y\).

> Instead of a point estimate for \(\theta\), and a point estimate for \(y\) given a new observation \(x\) (which makes use of \(\theta\)), we have distributions for each.

Unfortunately, in complex systems with a non-trivial functional form and number of weights, this computation becomes intractably large. As such, in fully Bayesian modeling, we approximate these distributions. In classic machine learning, we assign them a single value (point estimate). It's a bit lazy, really.

Summary

I hope this post serves as useful context for the machine learning models we know and love. A deeper understanding of these algorithms offers humility—the knowledge that none of these concepts are particularly new—as well as a vision for how to extend these algorithms in the direction of robustness and increased expressivity.

Thanks so much for reading this far. Now, climb out of the pool, grab a towel and import sklearn.

Resources

I recently gave a talk on this topic at Facebook Developer Circle: Casablanca. Voilà the: